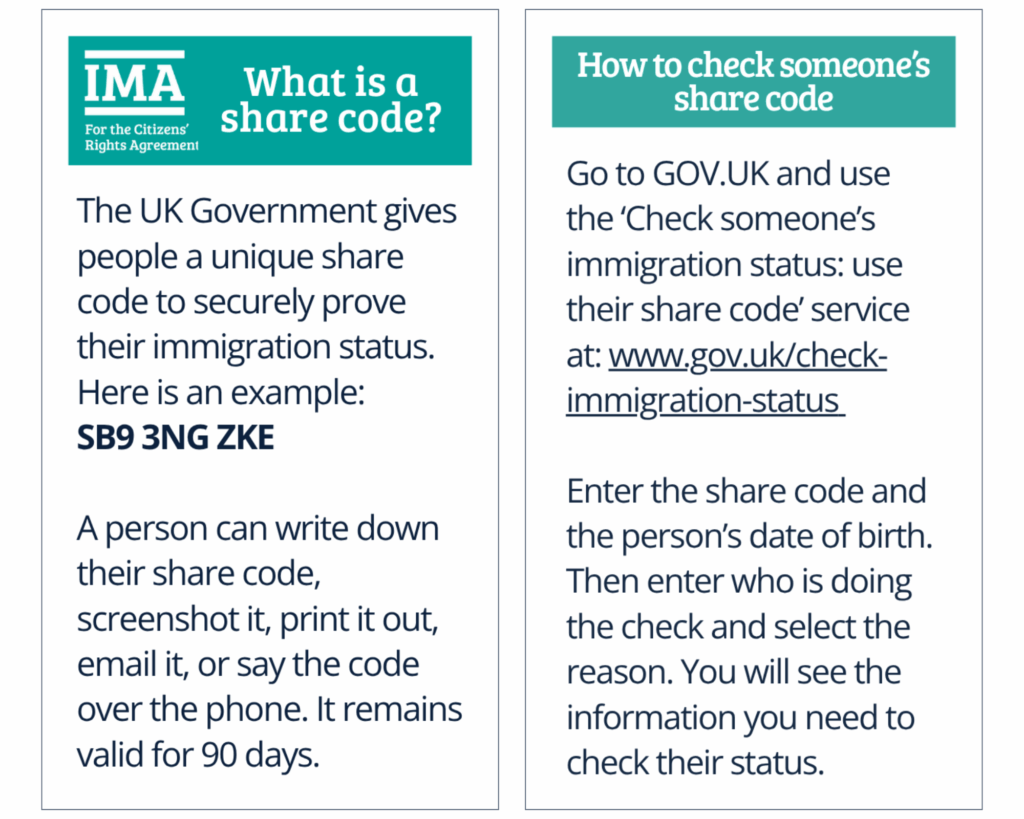

The UK Government gives people a unique share code to securely prove their immigration status. Here is an example: SB9 3NG ZKE

A person can write down their share code, screenshot it, print it out, email it, or say the code over the phone. It remains valid for 90 days.

How to check someone’s share code

Go to GOV.UK and use the ‘Check someone’s immigration status: use their share code’ service at: https://www.gov.uk/check-immigration-status

Enter the share code and the person’s date of birth. Then enter who is doing the check and select the reason. You will see the information you need to check their status.

Info card

If you need to quickly and easily explain what a share code is, and how someone can check it for you, download or screenshot our digital info card to keep on your phone.

(Preview)